Circuit tracing with the Qwen3 Cross-layer Transcoders

A circuit-level analysis of how Qwen3 produces specific predictions.

Cross-layer transcoders (CLTs) were originally developed to help find circuits in large language models. Circuits are collections of components in the model through which we can causally trace the model’s logic as it produces an output, explaining why the model produces the output it does for a given input. For a circuit-based explanation of a model to work well, it should do a few things.

The circuit should be made up of pieces we understand. In our case, these pieces will be groups of CLT features.

The circuit should tell a story. We should be able to identify different steps in the model’s computational process and why those steps make sense to do. For a particular prompt, we will look for computational connections between these groups of features.

Finally, the circuit should let us intervene in the model’s computation with predictable effects. To test this, we will steer groups of features and observe the effect on the model’s prediction.

The CLT-based approach to circuit discovery uses objects known as attribution graphs, which link together groups of CLT features into a network whose edges represent causal influences of one feature on another. To build our example, we will use the open source circuit-tracer library, along with our recently released Qwen3 cross-layer transcoders. Together, these tools let us explore how the model links different pieces of information about an individual to infer that individual's name, using the following prompt:

Fact: The president of the United States in 2010 was

Qwen3-1.7B correctly completes this prompt with the next token “ Barack”, assigning a 74% probability to this token, with an additional 7% probability for the token “ Obama”. We want to understand how it determines that Barack Obama is the correct completion of the sentence.

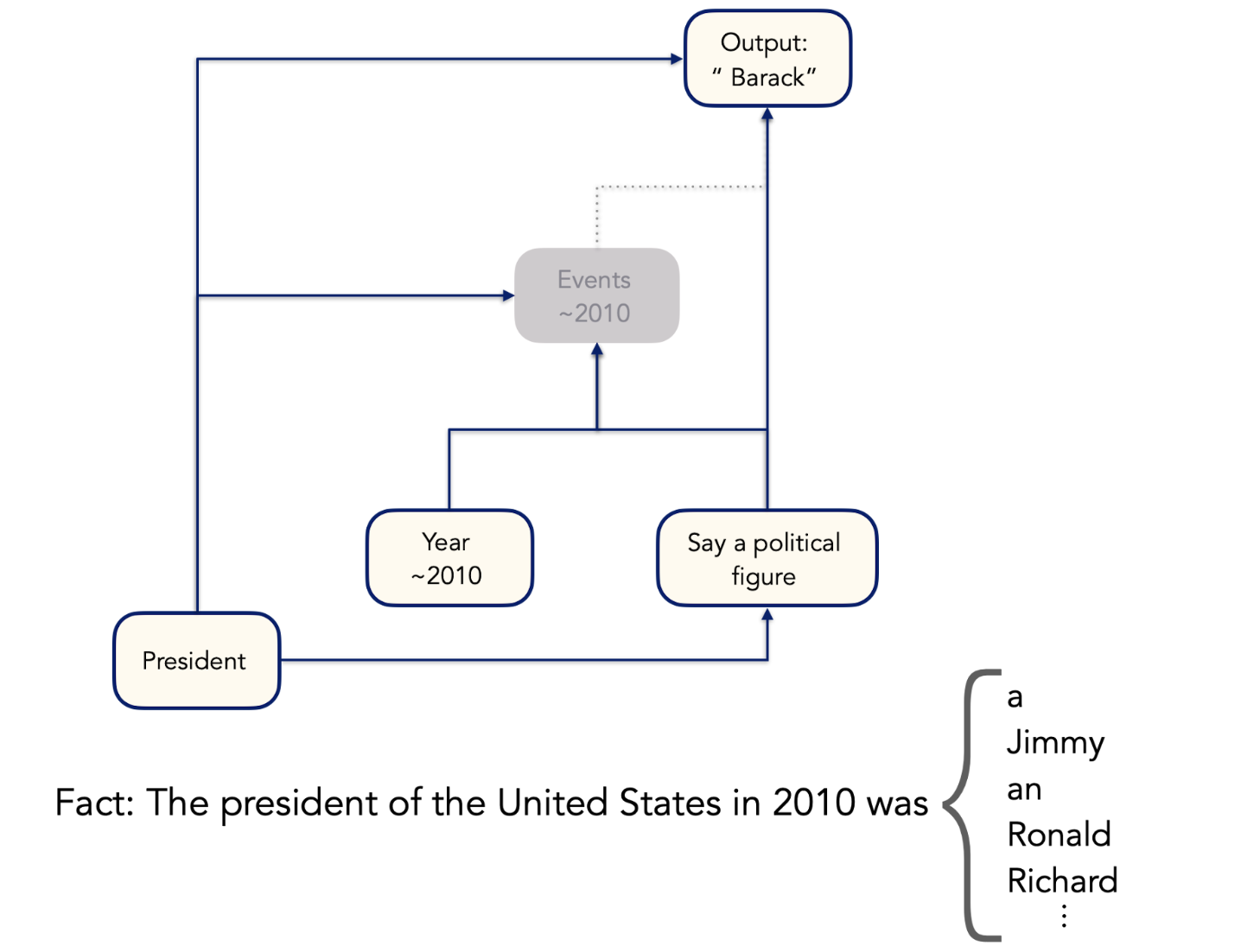

Our full analysis is available to explore in this Colab notebook. We find four key groups of features that help the model produce the correct output, and their relationships are represented in the following diagram.

The first is a group of features that activate when the model sees the token “ president”, and reinforces this concept throughout the rest of the attribution graph. This group of features has a direct effect on the output token, as well as on most of the other feature groups. Another group of features activates when the model reads the tokens in the year “2010”. These features represent years in the general vicinity of the year 2010. Different features have different levels of specificity—some features respond broadly to any year in the 2010s, while others activate only for years very close to 2010.

The “President” features help trigger a group of features that are active when the model is processing the final token “ was”. This group of features encourages the model to generate the name of a political figure next. (Note that the model might otherwise continue this sentence with a word like “the”.) A final group of features is activated by all the previous groups of features, and represents events that happened around the year 2010, with varying levels of precision. Together, these features combine to produce the model’s prediction of “ Barack”. This makes sense: the intersection of “president”, “political figure”, and “happens in 2010” is in fact Barack Obama. (Note that the mention of “the United States” in the prompt doesn’t seem to have much direct effect on the model’s output; this is likely because when the model thinks of presidents, it’s usually thinking of US presidents, so there’s no need to rely on the explicit statement.)

Let’s see what happens when we turn off some of these features. If we steer the “events ~2020” features down, the model now predicts presidents from the 70s and 80s.

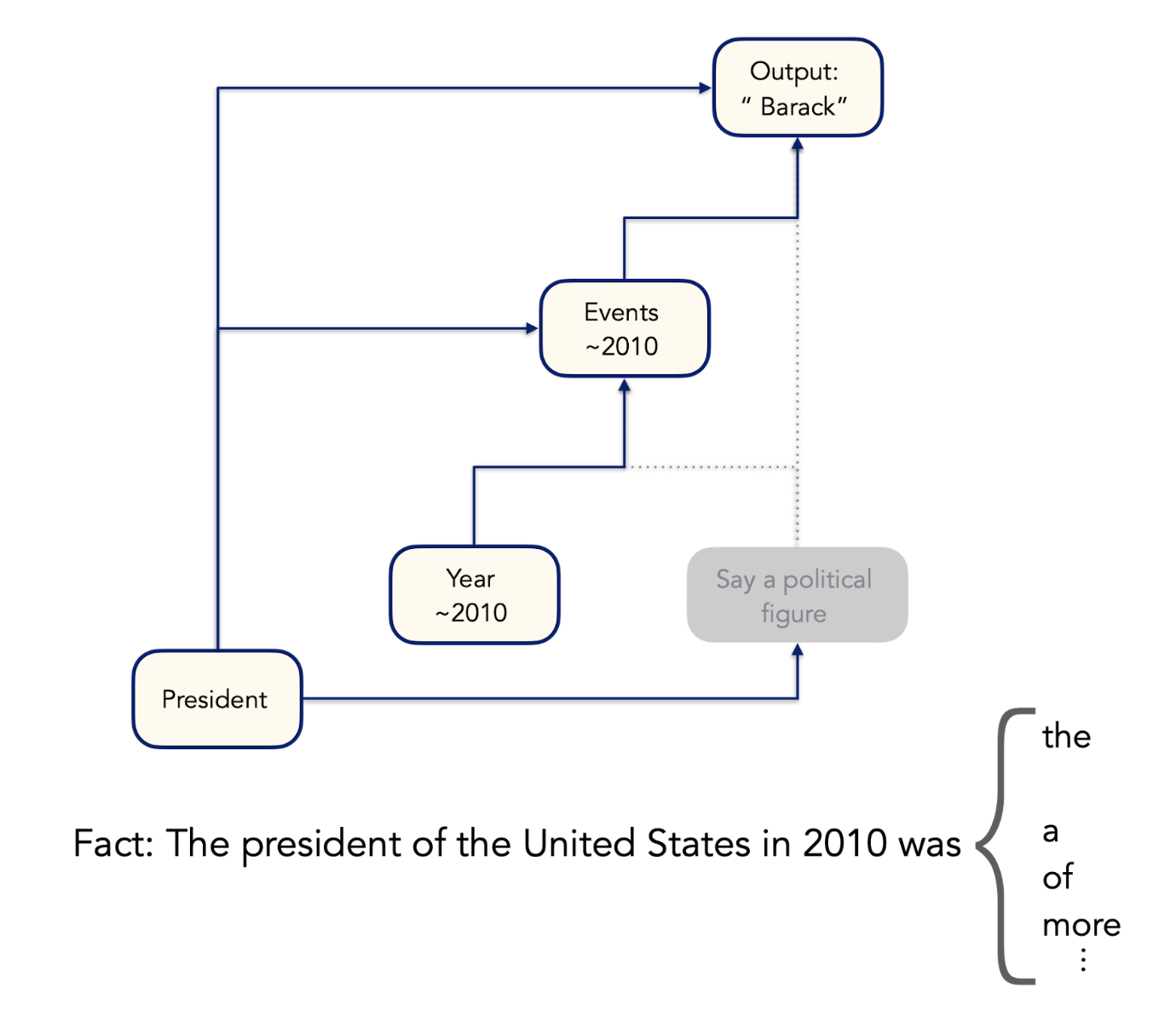

If we ablate the “Year ~2010” features, the model predicts a wide range of presidents, although none from the 2010s:

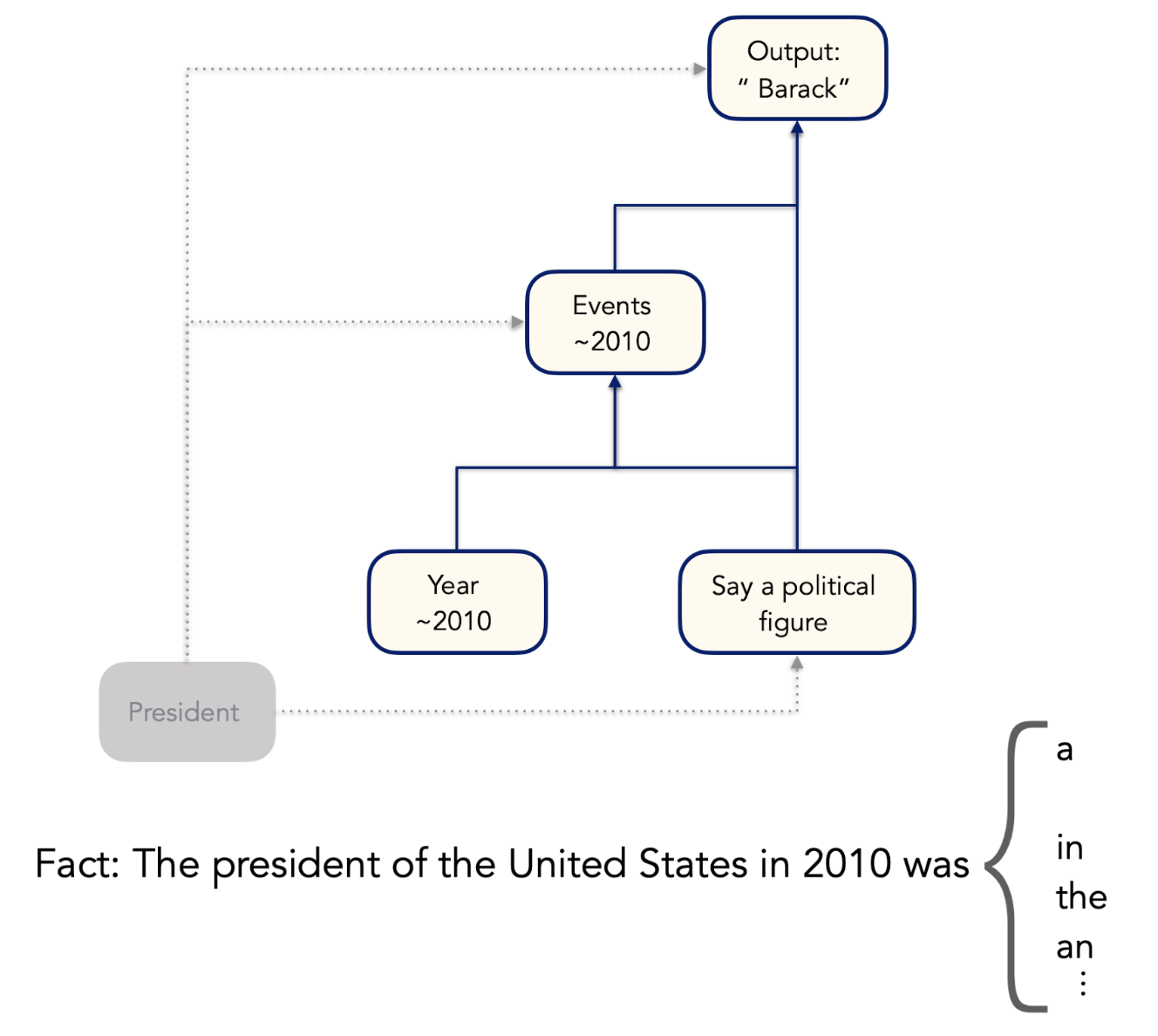

Removing the “President” or “Say a political figure” features results in the model predicting grammatically correct but uninformative filler words:

This makes sense: if the model does not know it’s looking for a president or needs to say the name of an individual, it will try to continue the prompt in a reasonable way without committing itself to a particular claim.

By performing this circuit tracing process, we’ve gained some small but very real insights into how Qwen retrieves information and makes predictions. However, building attribution graphs still requires a significant amount of manual effort to get even these small wins. We’re working hard on tools that will help automate this process and decrease the amount of work needed to get insights into models and datasets.